During World War II, the South Pacific skies were filled with cargo planes. These planes, flown by Allied forces, would land on the islands of Melanesia and unload boxes of canned food, clothing, cigarettes, weapons, and other goods. The native people of these islands were amazed. In their multiple thousand-year history they had never seen anything like it.

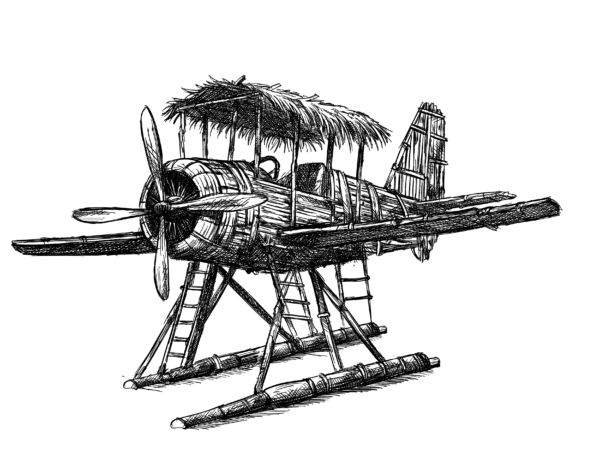

When the war ended and the planes returned home, the South Sea islanders wondered what had happened. They noticed the aircraft had landed on airstrips with air traffic towers, lights, and other airplanes. So they did the most logical thing they could think of: they created airstrips, aircraft, and traffic towers of their own, made out of wood, bamboo, palm leaves, and whatever else they had. And they waited for the cargo planes to land.

These events have since been dubbed “cargo cults” 1 and they lasted for years. It’s easy for someone on the outside to chuckle at this, maybe even to find it ridiculous. But the South Sea islanders’ behavior makes a lot of sense if you think about it. With no further information or context, why wouldn’t a cargo plane appear and land when you created all the apparent conditions for it?

The rest of us aren’t as different from the native islanders as we might think (nor are they different from us). Most of us are taken in by cargo cult thinking; the only thing that differs is the form that the “cargo” takes.

We Use Cargo Cult Thinking Everywhere in Life

Our brains have evolved to see connections everywhere and to make those connections as simple as possible. This often means making connections that don’t exist. Another term for this is “illusory correlation.”

In a 1960’s experiment, researchers showed the participants pairs of words, some of which were emotionally or thematically suggestive, such as “lion” and “cancer.” The word pairings were random but the researchers found that the participants saw connections or themes between certain words—especially the emotionally-charged ones—leading them to believe the pairs occurred together more often than they did.2

We engage in cargo cult thinking, including illusory correlation, without realizing it. This is why it’s so pervasive. It exists in business, in politics, even in science organizations and academia – anywhere that involves “cargo” (money, influence, gratification). It can look like the following:

- An aspiring entrepreneur who wakes up at 5 AM because that’s what most successful CEOs and entrepreneurs supposedly do

- A boss who tells their employees to adopt a new software because their competitors are also using it

- A government that adopts a policy that’s worked in other countries, without understanding contextual differences

Cargo cult thinking can even influence innocuous things like clothes and eating habits – think of the now-disgraced entrepreneur Elizabeth Holmes wearing black turtlenecks and drinking green smoothies in imitation of Steve Jobs. Green smoothies won’t make you a billionaire, but it’s tempting to focus on little tangible things instead of deeper, boring concepts like hard work.

Cargo cult thinking affects our personal lives in ways that are less obvious but no less serious. I’ve known more than one person who assumed that because married people are statistically happier, it follows that getting married therefore leads to happiness. Conversely, some assume that because the divorce rate hovers at around 50%, their odds of divorce are no different.

I’ve found myself, like thousands of others, assuming that home ownership is a solution to feeling secure in life. Is this sensible or is this, once again, conflating something shallow with deeper principles? Cargo cult thinking can be the subtlest of traps; to escape it you must fight continually.

“Leaning Over Backwards” to Get at the Truth

In 1974, legendary physicist Richard Feynman addressed the graduating class at Caltech. In his remarks, he targeted “Cargo Cult Science” (cargo cult thinking related to science). The problem, Feynman points out, is that people want to confirm their beliefs, which is exactly the opposite of how science should work. The solution, he goes on, is “a kind of scientific integrity”:

“It’s…a principle of scientific thought that corresponds to a kind of utter honesty—a kind of leaning over backwards. For example, if you’re doing an experiment, you should report everything that you think might make it invalid—not only what you think is right about it.” 3

I believe that this “principle of integrity” Feynman is describing can be extended to all areas of life, not just science. Note that it’s also extremely hard to do. People don’t want to be wrong, and they especially don’t want to spend extra time and energy “leaning over backwards” to find out if they’re wrong. It flies in the face of our instincts.

“The first principle is that you must not fool yourself – and you are the easiest person to fool.”

This is especially true in the everyday aspects of life. If we’re not running an expensive experiment or building a nuclear reactor, it’s easy to assume the stakes aren’t that high – but they are. The consequences of marrying (or not marrying) for the wrong reason, of patterning our lives after our friends and coworkers, of jumping to the easiest conclusion about any new information can set our lives on a disastrous trajectory.

Is there any memorable solution, or do we just need to grit our teeth and hit “manual override” every single time?

While there are no hacks or shortcuts to avoid cargo cult thinking (it would be ironic if there were), Feynman offers this pithy, fridge-worthy advice: “The first principle is that you must not fool yourself – and you are the easiest person to fool.”

In a way, this is great news. It’s easy to see the fault in others’ beliefs, but you can’t control others. Conversely, you are the easiest person to fool, but you also have control over yourself. A corollary we could add here is: “It’s even easier to not be fooled if you and others are watching out for each other.” Wise friends are a life preserver in the stormy seas of information, phenomena, life events, and decision-making.

The next time you are not getting the results (cargo?) in life you want, ask if you’ve engaged somehow in the subtle trap of cargo cult thinking. We all do it; we’re all programmed to do it. The only shame is when we make no effort to be better. And just like with anything important in life, we can become better by degrees. We may never be sages, but we can at least learn not to be fools, and that’s enough for us to win at life.

***

Read Next: Why We Can’t Predict What Will Make Us Happy →

Footnotes

- Some anthropologists have taken issue with the word “cult” in this context; they think it has too much baggage.

- Chapman, L. J. (1967). Illusory correlation in observational report. Journal of Verbal Learning and Verbal Behavior, 6(1), 151-155. You can read it here.

- Caltech. (n.d.). Cargo cult science. Caltech Library. Read the full speech here.

One response to “The Subtle Trap of Cargo Cult Thinking”

Sage advice for sure. Maybe we can remember to use the equivalent of that scientific integrity, personal discipline, and ask ourselves if this is the best choice or just what we’re looking for? You’re probably right, grit our teeth and hit “manual override”! Thanks for a great article!