“Become what you are, having learned what that is.”

This line from the ancient writer Pindar struck a chord in the heart of a very young Friedrich Nietzsche, influencing him and his philosophy for the rest of his life. It’s a riddle that’s puzzled people throughout the ages. How do we become who we already are?

Sometimes it’s easier to address a hard question by first addressing an easier one. A more common phrase we throw around is “finding yourself.” How do you “find yourself” when you’re already walking around in your own body (or, if you’re a materialist, you are your body)? More people have a ready answer for this one. “Well, of course, you don’t literally find yourself,” they snort, with amusement and maybe faint derision. “You have to, you know, go do some things. Try things. Maybe travel for a while.” Often the traveling is to a far-flung destination, maybe India or Japan.

At a glance, “finding yourself” and “becoming yourself” – or “becoming what you are” – look like poetic ways of saying the same thing. The two, however, could not be more different.

The Self Is Created, Not Found

“Finding” and “becoming” both imply action. But here is where the similarities end. “Finding” implies that your self is out there, somewhere, and once you find it you will “have” it. “Becoming,” on the other hand, is an ongoing state.

The poet and novelist Robert Penn Warren expounds on this idea:

As a last irony, let us turn to the words so frequently uttered by the yearning young — and, as a special phenomenon of our time, by the yearning not quite old, as well: “I am going to take time off and find myself.” “Time off” from school, from job, from [spouse] — from what? Free time: “to get away from it all” — whatever “all” is. But the key phrase is “to find myself.” 1

A quick interjection: I’ve always hated the phrase “to find myself.” I admit a bias here and agree with Warren that there’s something whimsical and vague about it.

He continues:

“In the phrase lurks the idea that the self is a pre-existing entity, a self like a Platonic idea existing in a mystic realm beyond time and change. No, rather an object like the nugget of gold in the placer pan, the Easter egg under the bush at an Easter-egg hunt, a four-leaf clover to promise miraculous luck. Here is the essence of passivity, to think to find, by luck, one’s quintessential luck. And the essence of absurdity too, for the self is never to be found, but must be created, not the happy accident of passivity, but the product of a thousand actions, large and small, conscious or unconscious, performed not “away from it all,” but in the face of “it all,” for better or worse, in work and leisure rather than in free time.”

Although appealing at first, the visual of finding my “self” like a gilded egg on Easter morning under a hedgerow is absurd when I think about it. Epiphanies and flashes of insights do occur, but most of life flows like water downhill, wherever the current takes it unless we redirect through constant effort and reflection. A change of scenery may jump-start some of our personal development, but if we want a deep sense of self we must toil at work and more importantly, concentrated leisure – as Warren points out. This we can do in an Alpine hut or just as easily within the walls of our homes.

This intentional type of living means that while we can’t control all the experiences we have, we can choose how to let them shape us. If anyone understood this, Nietzsche did.

We Are the Helmsmen of Our Existence

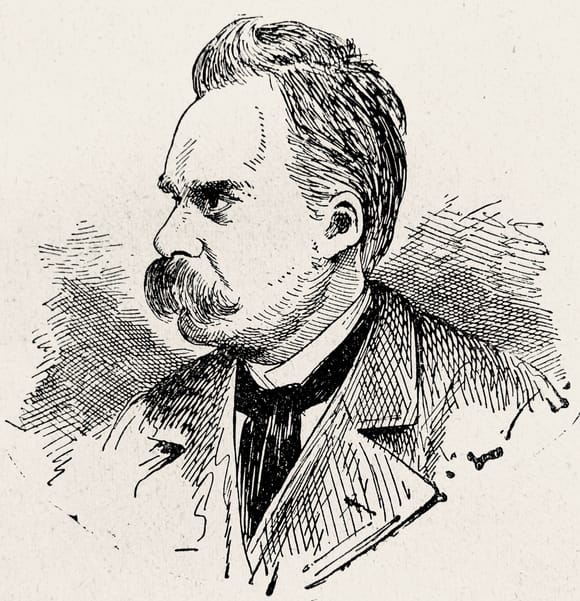

In the 1860s, Nietzsche’s star was rising. At just 24 years old he became a professor of classical philology at the University of Basel. He wrote several well-received papers and was respected by his colleagues. He was on what looked like a well-secured path to success and respectability.

Nietzsche enjoyed his job but he wanted to expand his horizons. His mind burned with the questions of existence. He longed to switch from teaching philology to teaching philosophy. Then he wrote his first book, The Birth of Tragedy, and his life took a sharp turn.

The Birth of Tragedy was a flop. It sold only a few copies and critics attacked it as weird and radical. One vicious review, in particular, devastated his reputation. Nietzsche’s university lectures went from 21 students in the summer of 1872 to only 2 students that following winter semester. If this was all he had to deal with he might have hung onto university life, but it wasn’t.

“We are responsible to ourselves for our own existence; consequently we want to be the true helmsman of this existence and refuse to allow our existence to resemble a mindless act of chance.”

From the time he was a child, he suffered from a combination of migraines, digestive problems, and eyesight issues; as he grew older, they worsened. At times the pain was so bad that he couldn’t work, read, write, or even see very well and he would vomit constantly. But Nietzsche was undaunted. Understanding the need to become who he was, he wrote: “We are responsible to ourselves for our own existence; consequently, we want to be the true helmsman of this existence and refuse to allow our existence to resemble a mindless act of chance.” 2

Nietzsche couldn’t get rid of his suffering, but he could at least use his suffering to shape his ideas and writing and make the most of his abilities. And continue to suffer he did.

His health issues became so serious that he quit his privileged job as a professor, never to return. For the rest of his life, he wandered and lived in different parts of Switzerland, France, Germany, and Italy, seeking warmer climate to ease his pain. Sometimes he was with friends; often he was alone. Most of his relationships with others broke down, including his long-term friendship with the composer Wagner. The woman he loved rejected his offer of marriage twice. He ran out of money. His health grew worse.

In late 1888, Nietzsche caught his breath and experienced a short but brilliant burst of energy. He wrote a flurry of pieces including his final, crowning work, Ecce Homo. In it, he confronts the conundrum of “becoming who you are”:

“To become what one is, one must not have the faintest notion what one is. From this point of view even the blunders of one’s life have their own meaning and value – the occasional side roads and wrong roads, the delays, “modesties,” seriousness wasted on tasks that are remote from the task.” 3

“Becoming who (or what) you are,” for Nietzsche, means embracing every aspect of your life, even the mistakes and sufferings. It means amor fati – to love your fate and not wish for it to be any different. At first, this might sound like a contradiction: how are we supposed to steer our lives if it means accepting whatever happens to us?

The answer, as the ancient Stoics knew, lies in understanding the difference between what we can and can’t control. We may suffer seizures, unfaithful spouses, or destructive floods but we can take each of these experiences and wrestle meaning and understanding from them to chart our course. This is what it means to be the helmsman of your existence.

Less than one month after he finished Ecce Homo, Nietzsche caused a public scene in the streets of Turin. To this day no one is sure exactly what happened, but by the end, he had a complete mental breakdown. 4 He would go on to live eleven more years but never regain his sanity. At the time of his death in 1900, his sister Elizabeth had complete control of his writings and appropriated them for the Nazi party. It would be years before his works and his ideas were restored to their true form.

Sometimes we continue to become who we are even after we die.

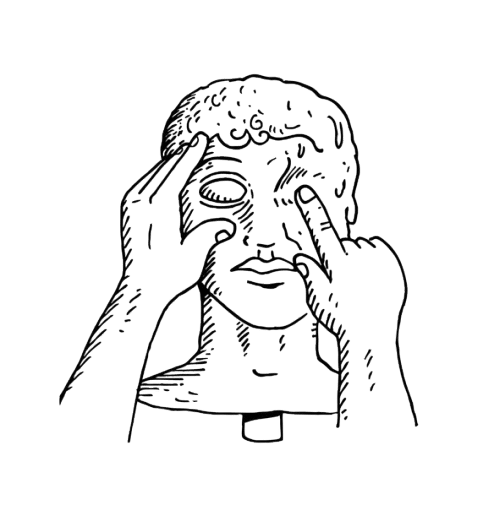

We Sculpt Our Lives

Contemporary author and philosopher John Kaag spent weeks hiking through the Alps, following the trails Nietzsche had trod. He ached to find meaning and insight to his life the way Nietzsche had over a century earlier.

Near the end of one of his trips, while watching a shepherd guide his flock across the Alpine landscape, he came to a realization similar to Robert Pen Warren’s:

As it turns out, to ‘become who you are’ is not about finding a ‘who’ you have always been looking for. It is not about separating ‘you’ off from everything else. And it is not about existing as you truly ‘are’ for all time.’ The self does not not lie passively in wait for us to discover it. Selfhood is made in the active ongoing process, in the German verb werden, ‘to become.’ The enduring nature of being human is to turn into something else, which should not be confused with going somewhere else. 5

Too often we’re obsessed with the idea of “finding” or “revealing” when there is nothing to find. We are lumps of matter and it’s up to us to mold that matter; but unlike a marble statue or piece of pottery, the molding process for us is never finished. Like fine china, we’re occasionally forced into the fire to emerge polished, shining, and resilient.

“It is a myth,” Nietzsche proclaims:

…to believe that we will find our authentic self after we have left behind or forgotten one thing or another … To make ourselves, to shape a form from various elements – that is the task! The task of a sculptor! Of a productive human being! 6

Becoming who you are is no mystical transformation, nor is it reaching some sort of final goal. Life is far more dynamic than this. It is an ongoing dance of acting and being acted upon. It requires being awake to everything we experience and intentional in what we decide to believe and do. It’s about choosing this over that, taking one path when someone in your shoes decides to take another. Above all, it is about endlessly learning, asking, and questioning. If we don’t do any of this, we aren’t much different from the rest of the animals.

Become what you are, having learned what that is.

***

Read Next: Braving the Wilderness: How to Live to Yourself →

Footnotes

- Warren, Robert Penn. Democracy and Poetry. Harvard University Press, 1975.

- Breazeale, Daniel, editor. Nietzsche: Untimely Meditations. Cambridge Texts in the History of Philosophy, Cambridge University Press, November 6, 1997.

Nietzsche, Friedrich. On the Genealogy of Morals and Ecce Homo. Edited by Walter Kaufmann, Vintage, December 17, 1989.- One popular story is that Nietzsche threw his arms around a horse, but this is most likely apocryphal.

Kaag, John. Hiking with Nietzsche: On Becoming Who You Are. Farrar, Straus and Giroux, September 25, 2018.- NF-1880,7[213] — Unpublished Fragments End of 1880.”