In 1838, Charles Darwin was mulling over a tough decision that many of us today can relate to: whether or not to get married.

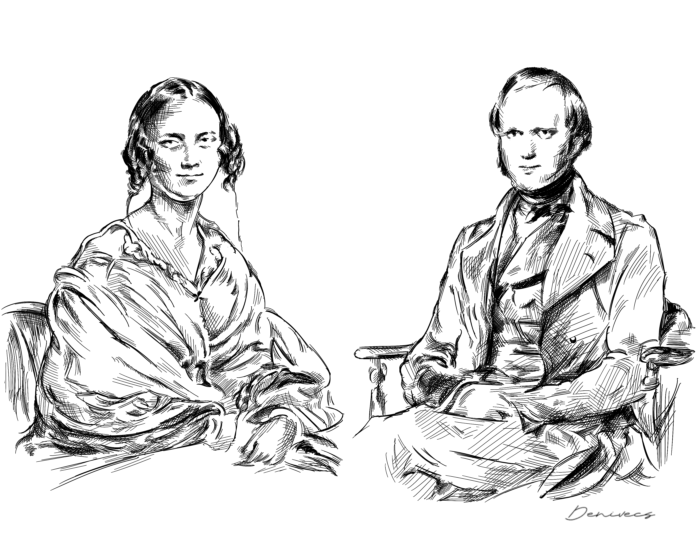

The person in question was Emma Wedgewood, his cousin.

Darwin was 29; Emma was 30. Both had had their share of life experiences; Darwin was a budding scientist who had traveled to Africa, South America, and Australia to study geology. Emma was an accomplished pianist who had briefly studied under Chopin, enjoyed archery, and toured Europe.

The two were already good friends who enjoyed occasional chats by the fireplace. But things had come to a crossroads; Darwin was advancing in his career and research, and he was afraid that a relationship (and children) would interfere with his progress. On the other hand, the thought of being alone forever also sounded less than ideal. If there was anyone he could see himself being happy with, it was Emma.

How was he to decide?

Part of why Darwin struggled for months over whether or not to get married was because he’d already realized something important that many others never do: there is no way for us to get everything we want in life.

Any choice we make between two good, valid options means that we’re missing out on the option we didn’t pick. This means we have to trust ourselves to choose the best (or least bad) option of all the options available to us. It may even mean choosing not between something better and something worse, but between two things that are equally good but different.

Finally, it also means we have to take ownership of whatever happens – both good and bad – as a result of our choice, for the rest of our lives. Think about that too long and you’ll want to crawl under the covers and dissociate with a pint of Ben and Jerry’s.

Everything Is a Trade-Off. Including Marriage

Darwin turned to journaling to figure out what his head (and heart) wanted the most.

Because he knew that both marriage and singledom involved trade-offs, he wrote down the pros and cons of either choice.“If not marry,” he wrote in his notebook in April 1838, “Travel. Europe? America????” He continued: “If marry—means limited, Feel duty to work for money. London life, nothing but Society, no country, no tours, no large Zoolog. Collect. no books.” 1

Three months later, he still hadn’t made his mind up. Back to the notebook he went, and wrote down a further list of pros and cons of marriage. Some of them come across as politically incorrect by today’s standards – he describes a wife as “better than a dog, anyhow.” 2 But many are more than relatable to those of us today who are dealing with the same dilemma:

Darwin’s “Pros” for marriage:

- A “constant companion” and “friend in old age”

- The comforts of a shared home

- More to life than just work and career

- The opportunity to have and raise kids

Darwin’s “Cons” for marriage:

- Lack of freedom to go wherever you want

- Being “forced to visit relatives and bend to every trifle”

- The “expense” and “anxiety” that comes with raising kids

- “Quarreling”

- Loss of time

- Less money for other things (in his case, “books”)

- Less time for nights out with friends 3

Unsurprisingly, the “cons” in his journal tended to outweigh the pros. Perhaps that’s because humans have a primitive tendency to focus on the negative more than the positive to protect themselves from harm. 4

In the end, for Darwin, it came down to the long-term outlook: he could either sacrifice certain material comforts in the near future or accept the fact he would grow old and die alone without someone to share his deepest thoughts with. You can follow this train of thought in one of his final paragraphs on the subject:

But then if I married tomorrow: there would be an infinity of trouble & expense in getting & furnishing a house,—fighting about no Society—morning calls—awkwardness—loss of time every day. (without one’s wife was an angel, & made one keep industrious).Then how should I manage all my business if I were obliged to go every day walking with my wife.— Eheu!! I never should know French,—or see the Continent—or go to America, or go up in a Balloon, or take solitary trip in Wales…And then horrid poverty, (without one’s wife was better than an angel & had money)— Never mind my boy— Cheer up— One cannot live this solitary life, with groggy old age, friendless & cold, & childless staring one in ones face, already beginning to wrinkle. 5

It’s an understandable dilemma: travel the world, have more money and free time to yourself…or invest in a warm and loving relationship that will, God willing, see you through to the end of your days.

His mind made up, Darwin proposed to Emma Wedgwood on November 11, 1838. She accepted his offer, and together they enjoyed a close companionship that lasted 43 years, until Darwin’s death.

But that’s not the end of the lessons we can learn from Charles and Emma Darwin, nor was their happiness in marriage a matter of luck.

A Leap of Faith is Required (and That’s Normal)

Soon after they became engaged, Darwin wrote a letter to Emma confessing:

“I think you will humanize me, & soon teach me there is greater happiness, than building theories, & accumulating facts in silence & solitude. My own dearest Emma, I earnestly pray, you may never regret the great, & I will add very good, deed, you are to perform on the Tuesday: my own dear future wife, God bless you.” 6

Darwin admitted here what he had not (yet) been willing to admit to himself in his private notebook: Marriage has the potential to make us a better person.

The happiest kind of marriage requires humility, even before we make the actual vows. If we believe that we already have everything within ourselves to reach our fullest potential, we shut the other person out of our journey. We miss out on helping each other grow.

This type of attitude shift does not come naturally. It requires a leap of faith; we haven’t changed yet, but we’re willing to change once we start down that path with the person we’ve entrusted our entire future to.

Paradoxically, we’re happier in marriage when we commit first – rather than wait for happiness before committing. Darwin realized he couldn’t be certain about the future, but he was willing to trust, and that set him and Emma on a sturdy foundation.

It Helps When You’re Able to Talk About Anything

Charles and Emma Darwin faced two major challenges in their 43 years of marriage: the death of three of their children (they had ten in total), and Darwin’s growing agnosticism.

The latter was a chronic challenge for Emma, who continued to be a devout believer in both God and the Bible. Differing worldviews are inevitable to some point with any two people, but they can also put a strain on relationships – what to do when this happens?

For Charles and Emma Darwin, the key was openness. In a letter written soon after their engagement, Emma told Darwin:

My reason tells me that honest & conscientious doubts cannot be a sin, but I feel it would be a painful void between us. I thank you from my heart for your openness with me & I should dread the feeling that you were concealing your opinions from the fear of giving me pain … my own dear Charley we now do belong to each other & I cannot help being open with you. 7

In their letters to each other they discussed matters of faith, doubt, inquiry, and belief. They addressed the elephant in the room rather than try to pretend it didn’t exist. Not every couple will struggle will the same difference in belief that the Darwins did, but every person in a relationship will feel vulnerable and different in some way from their partner.

Being able to trust in your partner enough to talk about anything on your mind – without fear of judgment or indifference – is the cornerstone of a solid and lasting relationship. Everyone must weigh the pros and cons of marriage for themselves, but the Darwins are a great example of how taking that leap of faith can lead to better things than almost anything else in life.

Yes, even better than a dog. (Well, maybe it depends on the dog).

Read Next: The Truth About Soulmates →

Footnotes

- “About Darwin: Family Life – Darwin Marriage.” Darwin Correspondence Project, University of Cambridge. https://www.darwinproject.ac.uk/tags/about-darwin/family-life/darwin-marriage.

- I’m not sure if that’s a greater insult to dogs, or potential spouses

- In his words, “Conversation of clever men at clubs”

- See Baumeister, R., Bratslavsky, E., Finkenauer, C., & Vohs, K. D. (2001). Bad Is Stronger than Good. Review of General Psychology, 5(4), 323. https://doi.org/10.1037/1089-2680.5.4.323

- “About Darwin: Family Life – Darwin Marriage.” Darwin Correspondence Project, University of Cambridge. https://www.darwinproject.ac.uk/tags/about-darwin/family-life/darwin-marriage.

- Darwin, C. (1839, January 20). Letter No. 489. Darwin Correspondence Project. Retrieved from https://www.darwinproject.ac.uk/letter/DCP-LETT-489.xml

- “Letter no. 441.” Darwin Correspondence Project, University of Cambridge, 29 June 2009. Web Archive. https://web.archive.org/web/20090629225121/http://www.darwinproject.ac.uk/darwinletters/calendar/entry-441.html.