Almost everything is better when we first imagine it, compared to when we first attempt it.

It’s true for almost anything you can think of: the art you create, the skills you practice, the relationships you nurture, even the chicken curry you cobble together for a weeknight dinner. On a normal day the strife is bearable. But there are days – too many of them – where we feel like we’re doomed to mediocrity, or worse, sliding backwards.

The obvious thing is to blame our flawed mortal brains and bodies. It doesn’t occur to us that our imaginations, as incredible as they are, might share just as much of the blame.

Struggle and Imagination: Two Sides of the Same Coin

Humans are the only animals with imaginations.

This is the source of much (if not most) of our anxiety. My dog is asleep in her daybed next to me as I write this; one glance at her is an enviable reminder of how she lives moment to moment, never worrying or wondering what will happen next or comprehending that anything could be different than it is.

For that same reason, my dog will also never write the next Pulitzer prize-winning novel or bestselling fantasy series. She doesn’t – she can’t – conceive of something that does not yet exist but could. This is the trade-off we make for being “enlightened”: we’re excited, even thrilled by what’s possible, and we’re discouraged and disheartened when it fails to materialize.

The only hope to taming anxiety and coming anywhere close to appeasing our imaginations is through honest, patient struggle. Alain de Botton, the gentle sage of the 21st century puts it this way:

“No one is able to produce a great work of art without experience, nor achieve a worldly position immediately, nor be a great lover at the first attempt; and in the interval between initial failure and subsequent success, in the gap between who we wish one day to be and who we are at present, must come pain, anxiety, envy and humiliation. We suffer because we cannot spontaneously master the ingredients of fulfilment.” 1

American writer James Lord illustrates this point vividly when he tells the story of sitting for his portrait by the great Swiss painter and sculptor Alberto Giacometti. During their many sessions together, Giacometti struggled with angst, frustration, and occasional rage over not being able to paint Lord’s portrait exactly the way he wanted to. Lord notes:

“This fundamental contradiction, arising from the hopeless discrepancy between conception and realization, is at the root of all artistic creation, and it helps explain the anguish that seems to be an unavoidable component of that experience.”

He goes on to add that harmony between Giacometti’s imagination and reality “was of course impossible, because what is essentially abstract can never be made concrete without altering its essence.” 2

Our imagination produces wonderful thoughts and dreams, but without physical form they are mere chimeras. The struggle to create something out of them is much more fulfilling than to live in a fantasy.

The implication here is profound. Lord is suggesting that when we create something, it will inevitably be a new and different thing from what we imagined. The book, the painting, the recipe, the relationship, the job…whether it’s better or worse, it won’t be the thing we’d had in our minds. I can see why this terrifies so many would-be creators; I’ve experienced it plenty of times myself, even during casual conversations when I couldn’t summon words for the thought in my head.

But there is a positive side here, too: the new thing can be far better than we’d imagined, or at least more complex and whole. Our imagination produces wonderful thoughts and dreams, but without physical form they are mere chimeras. The struggle to create something out of them is much more fulfilling than to live in a fantasy.

Imperfectly Realized Is Better than Perfectly Imagined

If there is one thing that plagues us in the digital age, it’s the allergy we’ve developed to any kind of struggle. At the first sign of discomfort we reach for the nearest source of dopamine: food, music, and most of all our devices.

It’s easy to rationalize these habits as necessary to help us cope with everyday stress, but we pay a high price if we do it too much or too long: our dreams with wither and die, our potential will never be realized. Holocaust survivor Viktor Frankl was far more familiar with struggle and discomfort than most of us will ever have to be, and what ultimately helped him survive was to embrace the struggle rather than minimize it:

“What man actually needs is not a tensionless state but rather the striving and struggling for some goal worthy of him. What he needs is not the discharge of tension at any cost, but the call of a potential meaning waiting to be fulfilled by him.” 3

The next time you feel the canvas or computer screen is mocking you, ask yourself if the thing you’re looking to accomplish is worthy of you. If it is, it won’t come easily. It shouldn’t. As wonderful and important as imagination is, we are capable of learning, creating, and achieving far greater things than imagination alone. It takes effort, experimentation, discovery and yes, struggle if we want to achieve something we can feel proud of.

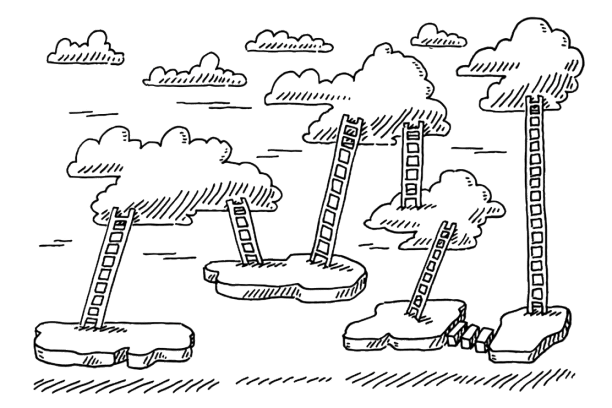

In her sharply observed book The Creative Habit choreographer Twyla Tharp notes, “Leon Battista Alberti, a fifteenth-century architectural theorist, said, ‘Errors accumulate in the sketch and compound in the model.’ But better an imperfect dome in Florence than cathedrals in the clouds.” 4

Perfection does not exist in real life, not in any measurable way. And in the struggle to create something worth sharing, worth doing, we ourselves are transformed in ways even we could not have imagined.

***

Read Next: How to Become Who You Are →