“Without great solitude, no serious work is possible,” Picasso supposedly once said.

In his words is a subtle challenge: If you want to do anything great in life, you will have to sacrifice time with other people, including those you love.

The word “solitude” itself is a double-edged one.

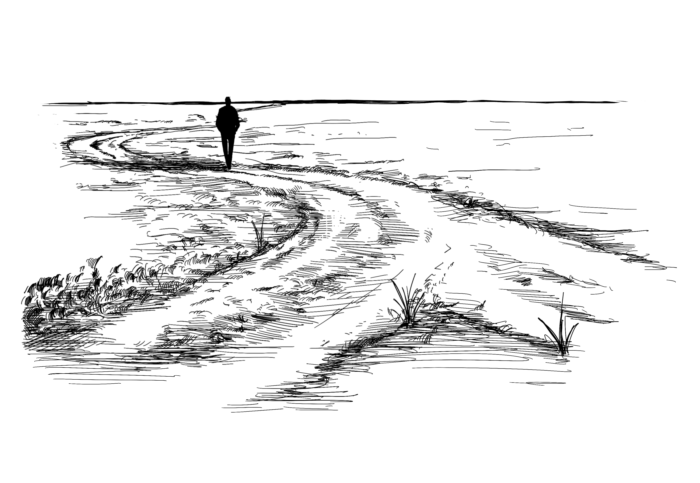

Depending on who you ask, it might bring to mind a scene either of a poet dreamily wandering through a forest, or a prisoner suffering in a cell. If we are to take Picasso at his word, we might see solitude as something reserved for genius thinkers and creators who sacrifice love, family, and everyday comforts to reach their full potential in life.

So is solitude a good thing? The short answer is yes, with a few caveats.

Solitude Is Not the Same Thing As Loneliness

The science of solitude is frustratingly inconclusive. The benefits of solitude for each person seem to depend on several things: personality, mindset, and early childhood experiences – to name just a few.

But one thing is clear: there’s a big difference between choosing to spend time alone and being forced to spend time alone.

This solves our dilemma of the dreamy poet versus the prisoner: there’s no question that anyone forced into solitary confinement is at risk for psychic distress. Because they have no freedom and no autonomy over where they will go or what they will do next their solitude becomes a living hell.

On the other hand, the person who willingly seeks out time alone is a very different case study. In those quiet moments and hours, it’s possible to think new thoughts, make discoveries, create art, write poetry, solve theoretical math problems, and all the other things that lead to our personal development. Solitude has even been found to be linked to curiosity and optimism. 1

Not all of us will want to seek out solitude to the same degree, and that’s perfectly natural. But if we are not comfortable in our own company with our thoughts for any length of time then not only are we at risk of stunting our personal growth – we won’t be able to tolerate any unexpected quiet time we happen to find ourselves in.

Or in the words of author and psychologist Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi:

“Solitude is a problem that must be confronted whether one lives in southern Manhattan or the northern reaches of Alaska. Unless a person learns to enjoy it, much of life will be spent desperately trying to avoid its ill effects.” 2

“A Room At the Back of the Shop”

The 16th-century writer Montaigne wisely points out in his essay, “On Solitude,” that simply being alone or in a new place is not enough for one’s personal growth:

“That is why it is not enough to withdraw from the mob, not enough to go to another place; we have to withdraw from such attributes of the mob as are within us. It is our own self we have to isolate and take back into possession.” 3

He goes on to say that we must “haul our own soul back into our self. That is true solitude. It can be enjoyed in towns and in king’s courts, but more conveniently apart.” Then in one of his most memorable metaphors, he tells us that we must set up “a room, just for ourselves, at the back of the shop, keeping it entirely free and establishing there our true liberty, our principle solitude and asylum.”

If we follow Montaigne’s advice, our minds become a sanctuary rather than an uncomfortable place to dwell. Solitude does not even have to be a physical state, according to this definition – it’s a mental state. We can be in the middle of a forest, a raucous dinner party, or Times Square and find refuge in our selves.

It’s no surprise that the victims who best endure concentration camps, prison, and other horrific scenarios are the ones who have developed this ability to order their thoughts and find enjoyment in their own company. Those who can cultivate solitude on their own are more likely to be able to handle extreme situations including solitude that’s been forced on them.

Relationships Versus Self-Development

Does reaching our fullest creative potential require us to spend lots of time alone, as Picasso’s quote suggests? And if so, does this come at the expense of relationships with others, or even happiness itself?

The famed psychoanalyst Anthony Storr explores these and related questions in his book Solitude: A Return to the Self. He examines the lives of many famous loners, from Newton, Kant, and Wittgenstein to Beethoven and Franz Kafka, and whether their trauma and unconventional lifestyles were necessary for them to reach their fullest potential. (Storr himself had a traumatic childhood and a lifelong battle with depression).

At one point he asks:

“Would they have been happier if they had been able, or more inclined, to seek personal fulfilment in love rather than their work? It is impossible to say. What should be emphasized is that mankind would be infinitely the poorer if such men of genius were unable to flourish, and we must therefore consider that their traits of personality, as well as their high intelligence, are biologically adaptive. The psychopathology of such men is no more than an exaggeration of traits which can be found in all of us. We all need to find some order in the world, to make some sense out of our existence.” 4

All of us come into life with our own set of baggage as well as natural strengths. To assume that the roadmap to happiness is the same for all of us would be to assume that we’re all similar in our personalities and life situations.

One of the most courageous things we must ever do is carve out our own purpose for existing on this earth. For some, relationships may eclipse everything else while for others, a calling to an important life work may come front and center. 5

In any case, solitude and a sense of self are vital in helping us find that sense of purpose.

***

Read Next: The Hedgehog’s Dilemma: 3 Ways to Not Be Lonely →

Footnotes

- Weinstein, N., Hansen, H., & Nguyen, T.-v. (2023). Who feels good in solitude? A qualitative analysis of the personality and mindset factors relating to well-being when alone. European Journal of Social Psychology. https://doi.org/10.1002/ejsp.2983

- Csikszentmihalyi, M. (2008). Flow: The Psychology of Optimal Experience (1st ed.). Harper Perennial Modern Classics.

- Montaigne, M. de. (1994). The Essays: A Selection (M. A. Screech, Ed. & Trans.). Penguin Classics.

- Storr, A. (2015). Solitude: A Return to the Self. Free Press.

- Storr notes at the end of his book: “The happiest lives are probably those in which neither interpersonal relationships nor impersonal interests are idealized as the only way to salvation. The desire and pursuit of the whole must comprehend both aspects of human nature.” Similarly, when asked what made a meaningful life Freud responded, “love and work.”