The life of Joe Dominguez is not your typical rags-to-riches story.

He grew up in Spanish Harlem with a mother who never learned English and a father who lived in a TB ward. He relied on his brains to survive in a street gang, learning how to make explosives. In middle school, his teacher assigned him to write an essay on where he wanted to be in life by age 30. He answered, “Financially independent.”

Dominguez never graduated college but thanks to grit and a lucky connection he landed a job on Wall Street. For the next several years he learned to master the ropes and even helped develop some of the first tools of technical analysis. By 1969 he had saved up $100,000 – he declared that he’d reached his childhood goal, proceeded to move into a motorhome, and retired just shy of his 31st birthday. He spent the next 28 years volunteering and helping others learn to become financially independent.

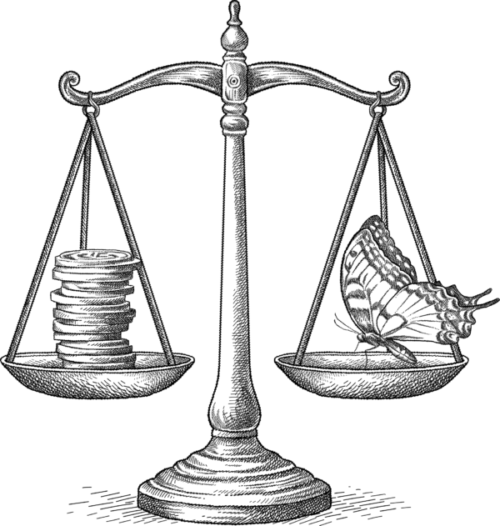

Why did this scrappy, gifted financial worker choose to leave a well-paid job to plant vegetables and teach free seminars for the rest of his life? Clearly for Dominguez, money was a means, not an end. Time and freedom were what mattered most. With the help of his partner Vicki Robin, he put together a series of lectures that eventually became a bestselling book: Your Money or Your Life. It continues to inspire new generations of readers today, even though Dominguez passed away in 1998. 1

Is Joe Dominguez a role model for the rest of us to follow, or an eccentric outlier? It’s one thing to aim for a “work-life balance”, but it’s quite another to voluntarily live off $6,000 per year for the rest of your life the way he did.

“Money doesn’t buy happiness,” most of us agree, but it sure seems to make a lot of things in life easier. Between the sleep-deprived Elon Musks and the bootstrapped Joe Dominguezes of the world surely there’s a middle ground – but what does it look like?

How much does money affect our well-being?

Cantril’s Ladder vs. Day-to-Day Emotions

It takes a brave person to come up with a number for “how much money” we need to feel happy, or at least well-off. In 2010, that brave person was actually two people: Daniel Kahneman and Angus Deaton. The “magic” number was $75,000. 2

Kahneman and Deaton arrived at this number by analyzing more than 450,000 responses to a survey that took almost an entire year to conduct. They used two types of questions with each respondent. The first approach was an exercise known as Cantril’s Ladder: imagine your life is a ladder with 10 steps; which step on that ladder do you see yourself at, with 0 being the worst possible and 10 being the best possible?

The second approach involved a series of yes-no questions that asked the respondents about their recent emotional state (“positive,” “stressed,” “sad,” etc). It measured feelings of well-being, compared to Cantril’s Ladder which measured a more general “idea” of how well respondents thought their lives were going as a relative whole.

Kahneman and Deaton found that respondents answered differently about money with the two approaches. When it came to Cantril’s Ladder, the more money the respondents had, the higher up the ladder they felt they were – and this number showed no sign of dropping off until $120,000 or even higher. On the other hand, when it came to questions about their day-to-day emotional state, there was no significant improvement in respondents’ mood levels once they were earning $75,000 or more per year. People who earned $100,000 per year were no less grumpy, anxious, or content than those who earned a quarter less.

It’s a famous study that’s been cited numerous times in the years since; it made such a splash after it came out that one company even adopted a $70,000 minimum wage for its employees, hoping to help boost their happiness levels.

Unsurprisingly, it’s drawn its share of detractors as well. “How can anyone possibly say that having more than $75,000 doesn’t increase your happiness?” people objected. “How do you even measure happiness, anyway?”

They have a point. Happiness isn’t like carbon or lithium or water. You can’t touch it, contain it, weigh it, or put it in a lab storage cabinet. Kahneman himself acknowledged at the end of his paper, “This topic merits serious debate.”

So in 2022, he decided to reopen the debate.

A Different Discovery

Daniel Kahneman was known for a unique approach when it came to doing research: “adversarial collaboration.” When someone objected strongly enough to one of his ideas or findings, he was willing to revisit the issue with them and see what new evidence both of them could find together.

In his follow-up study, he collaborated with two new researchers to try and find out, once and for all, if there’s a hard number that will guarantee our well-being. They used an experience sampling method that required participants to log into their phones several times a week and answer the question, “How do you feel right now?” on a continuous scale from “very bad” to “very good.” The idea was to gauge more accurately just how much of a difference money made toward individuals’ mental and emotional well-being. 3

This time, there was no point of diminishing returns: the study found that the higher the income, the happier the earner – at least up to $500,000 (far more than most of us will ever see at one time in our working lives). There was one interesting exception, however: a minority of the participants – around 20% – formed an “unhappy group” whose mood levels were not improved at all by additional income. For these people, the source of their unhappiness is apparently too deep to be improved by money alone.

Where do people like Joe Dominguez fit into this equation?

Are they naive fools who would have been happier had they only stuck to their jobs and traditional lifestyles instead of living a Thoreauvian life on a vegetable patch? Or are they bizarre exceptions to the rule that we can admire but not hope to emulate?

No matter how rigorous the research, it’s impossible to know with perfect scientific accuracy how something like happiness or contentment works. But I have a few thoughts.

First of all, there is the classic problem of causation versus correlation. There is no way to know that having half a million dollars will actually make you happier, especially long-term. Perhaps it will. But it could be that the people who earn high amounts have other qualities (like resilience, foresight, or positivity) that are the real cause of feeling “very good’ – the money is at least partly a by-product.

Also, even if individuals like Joe Dominguez are extremely unusual in how unattached they are to money and material possessions (allegedly, he never took money for any work he did the rest of his life, after retiring at 30), they still teach an important lesson to the rest of us:

Money is necessary and it’s great for a lot of things, but it’s not the be-all, end-all of life. In fact, not even close.

The Stoic View of Money: a “Preferred Indifferent”

The ancient Stoic philosophers would have agreed with Joe Dominguez that money is a means, not an end. In fact, they even had a term for it: “indifferent.”

In Stoic thought, an indifferent is something that’s neither good nor bad. You can use it for good or ill, but it’s neutral in and of itself. Money is a good example of a “preferred indifferent” – an indifferent that people tend to want or prefer. 4

Unlike many other ancient philosophers who lived convent-style lives, the Stoics were no strangers to wealth and status. Seneca and Cicero were extremely rich and politically well-connected (although they both met tragic endings). Marcus Aurelius was the emperor himself at one point.

But what made the Stoics different from their non-philosophical colleagues is that they knew how fleeting and fragile money and power were. They wrote about this fact; they obsessed over it. The key to true happiness – eudaimonia – was in having a tranquil mindset no matter what happened in life. Obviously, it’s far easier to do this when you’re not attached to your money to begin with. “Wealth consists not in having great possessions,” Epictetus once said, “but in having few wants.”

“Our inner work – the job of self-examination, self-development, and emotional and spiritual maturation – is just as crucial as paid work or housework or yard work.”

Still, there’s a bit of a conundrum here: how do we earn and grow our money without becoming attached to it? How does the CEO who spends 70 hours a week at the office keep from having his entire identity become his status, his paygrade?

This gray area is where the endless debate rages on. We can agree that it’s possible to have money and not be obsessed over it, but to what extent and in what proportion is the source of heated, sometimes even hostile discussion. The reason it’s so heated is that it’s personal. Just as Joe Dominguez and Seneca had to figure out their own relationship with money, based on their ultimate chosen purpose in life, we too have to form our own very personal relationship with money.

It would be nice to have a blueprint handed to us saying, “Here is exactly how much you need to be happy and not a penny more.” In fact, that’s probably why Kahneman’s original 2010 study became so commonly cited and along with that, grossly oversimplified.

Real life requires us to work for our own answers. Money is no exception.

Wisdom is the Key (But That’s Easier Said Than Done)

Needs are finite, but wants are infinite. Knowing the difference between the two – and knowing when you have “enough” – requires posessing a quality that is rarely mentioned or praised these days: wisdom.

Wisdom means having an accurate perspective. It means having a good (or good enough) set of values so that we’re not blown around by the wind, trying to forever keep up with the Joneses, or chase the latest shiny new thing. It goes deeper than that, even.

Most of us are sensible enough to realize that luxury SUVs and oceanfront properties are not things we need, as appealing as they may be. The much more difficult, insidious use cases are those that appear to be good and even necessary things that also require a seemingly endless well of money. Consider the following:

- “I have a million dollars in my retirement fund, but I need more to leave enough for my children”

- “I can’t retire yet – I need to make sure I have enough in my health savings account in case I come down with an autoimmune disease”

- “The more I have to give to charity, the more I can make this world a better place”

“Enough” is not a mathematical reality when it comes to money. There are too many variables in life, even for the most cautious and prudent of us.

But we will certainly be poor in spirit and intellect if we don’t make time for the development of our entire selves. Vicki Robin notes in Your Money or Your Life:

“Our inner work – the job of self-examination, self-development, and emotional and spiritual maturation – is just as crucial as paid work or housework or yard work. It takes time to know yourself – time for reflection, for prayer and ritual, for developing a coherent philosophy of life and personal code of ethics, and for setting personal goals and evaluating progress.”

Money will help us with some of these things, to some extent. But if we make it our biggest focus, even unintentionally, we will stunt our personal growth. And in doing so we will waste a resource far more valuable than any amount of money: our time.

***

Read Next: How Thinking About Death Can Make You Happier →

Footnotes

- You can learn more about Joe Dominguez’s life here and here.

- Kahneman, D., & Deaton, A. (2010). High income improves evaluation of life but not emotional well-being. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 107(38), 16489-16493. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1011492107

- Killingsworth, M. A., Kahneman, D., & Mellers, B. (2022). Income and emotional well-being: A conflict resolved. Edited by Timothy Wilson, University of Virginia, Charlottesville, VA. Received May 20, 2022; accepted November 29, 2022.

- Poverty, in this case, would be a “dispreferred indifferent”