There’s a common trait that successful creative people seem to share: a relentless drive to reach their dreams, no matter what.

Stephen King wrote his breakthrough novel Carrie on a typewriter in the laundry room of a rented trailer. Steve Jobs slept on the floors of friends’ homes and collected Coke bottles while auditing a calligraphy class that later helped him create unique typefaces for Apple.

But my favorite example of all is Octavia Butler, who wrote and clawed her way from a working-class life in Pasadena, California to become the first Black woman to write Hugo and Nebula-award-winning science fiction, and the first science fiction author of all time to be awarded the MacArthur Fellowship.

Butler had her own special term for this unwavering determination: “positive obsession.” “Positive obsession is about not being able to stop just because you’re afraid and full of doubts,” is how she explained it. “Positive obsession is…about not being able to stop at all.” 1

Obsession isn’t something we typically associate with a meaningful life, but maybe it should be.

It will look different for each of us, but the underlying principles are the same. For an idea of how we can achieve it, the life and career of Octavia Butler are ground zero.

“Why Not Me?”

By the time she was ten, Butler was typing stories two-fingered on the Remington she’d begged her mother to buy for her. At age twelve, she watched a terrible movie on TV called “Devil Girl From Mars” – and it changed her life forever.

“Geez, I can write a better story than that,” was her first reaction. A second realization hit her: “Gee, anybody can write a story better than that.” Her third epiphany was the biggest one yet: “Somebody got paid for writing that awful story.” 2

This realization was enough to light a fire under her tail; she got to work writing her own stories and submitting them to literary magazines. She got nothing but rejection slips for her efforts at first, but after enrolling in creative writing classes and finding a mentor, she finally sold her first story.

How did she persevere in the meantime?

“When I was older, I decided that getting a rejection slip was like being told your child was ugly,” Butler later wrote. “You got mad and didn’t believe a word of it. Besides, look at all the really ugly literary children out there in the world being published and doing fine!” 3

Butler felt motivated not just by reading and watching high-quality stuff, but by reading and watching mediocre stuff too. It made the bar seem lower and the goal seem more achievable.

Put simply: “If they can make it, why not me?”

Keep Your Eye on the Target

Butler was a shy, lonely girl who hid away in her school library behind a “big pink notebook” to avoid being bullied by her classmates. Instead of playing team sports, she chose to learn archery where she could compete against herself.

She saw parallels between archery and becoming a better writer: “Obsession can be a useful tool if it’s positive obsession. Using it is like aiming carefully in archery.” 4

Butler’s most immediate goal was to support herself full-time as a writer. Despite her mother’s suggestion that she work as a secretary, Butler stuck to menial, repetitive jobs that allowed her to preserve her mental energy for writing: she worked as a housekeeper, dishwasher, and at one point, a potato chip inspector.

Her focus paid off and by her early thirties, she was able to support herself full-time by writing. But she didn’t stop there. She dreamed of topping the bestselling lists and helping young aspiring Black writers follow in her footsteps.

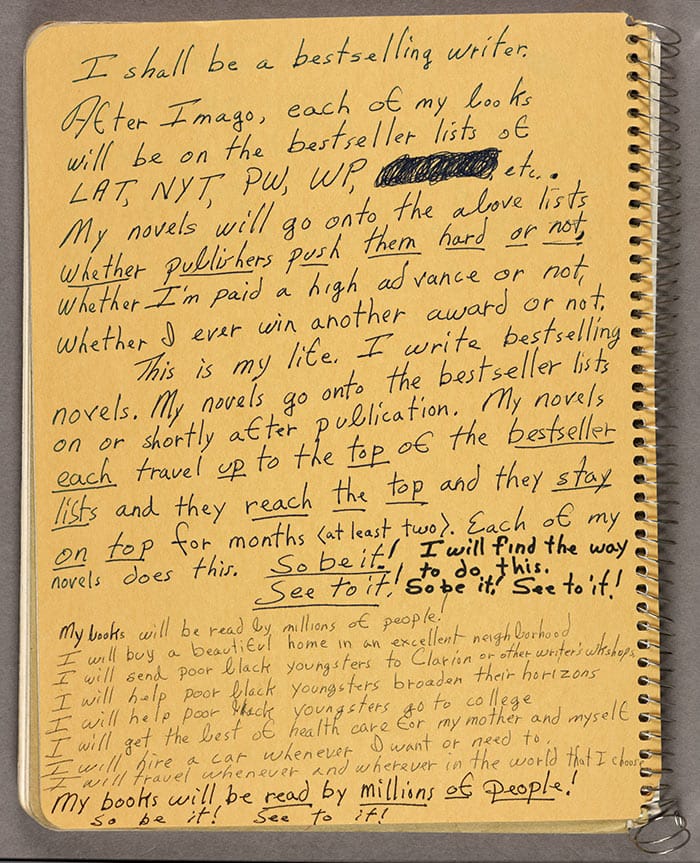

To keep her eye on her target she filled reams of notebooks, writing out her goals and affirmations where she could refer to them over and over.

Positive obsession means arranging your whole life around what matters most to you. It also means having constant visual reminders, whether it’s a notebook or a sticky note on your mirror.

We practice and repeat until it becomes a reality.

Find Your Calling and Create Yourself

In her short, modest but powerful essay “Positive Obsession,” Butler describes another pivotal event from her childhood:

“I think,” my mother said to me one day when I was ten, “that everyone has something that they can do better than they can do anything else. It’s up to them to find out what that something is.” 5

From that point on, in the back of Butler’s mind was the challenge, What is the thing I’m meant to do – the thing I can do better than anyone else? This prompt, subconsciously or not, guided her throughout the rest of her life.

Steven Pressfield, author of The Art of War, understood what Butler’s mother was getting at. “We come into this world with a specific, personal destiny,” he writes. “We have a job to do, a calling to enact, a self to become. We are who we are from the cradle, and we’re stuck with it.” 6

The first time I read his words, I strongly disagreed. We’re not pre-destined, I thought. We have many choices of what we can do, and we get to choose which one.

Pressfield is speaking paradoxically, though. He continues:

“Our job in this lifetime is not to shape ourselves into some ideal we imagine we ought to be, but to find out who we already are and become it.”

We only live one reality, so in hindsight, we are in a sense tied to a certain destiny. We have the choice between aiming to reach our potential or neglecting it.

Octavia Butler is a supreme example of someone who reached for goals that everyone around her (including at times her own family) thought impossible, and she went on to achieve even greater feats than perhaps even she imagined for herself.

During her lifetime she wrote multiple bestsellers, won the most prestigious awards available in science fiction, and blazed the trail for other Black writers of science fiction. Today she’s a household name in her genre and has a landing site on Mars named after her.

“Every story I create creates me,” Butler once wrote. “I write to create myself.” She understood the importance of becoming who you are and stopped at nothing to get there.

Here’s the question for you: what are you obsessed with? What are you willing to stop at nothing to accomplish?

Butler is an exceptional person, but even she didn’t consider her achievements to be a result of anything supernatural. She once described herself as “an oil-and-water combination of ambition, laziness, insecurity, certainty and drive.” 7 Full of grit, for sure, but no superhuman.

You might argue that Butler is unusual and lucky in that she was so laser-focused on her dream of being a writer. Maybe it even sounds romantic and unrealistic. Then again, maybe we’re wrong. Are we pulled into too many directions to ever achieve the thing (or things) we care about most, deep down?

If you don’t feel obsessed or driven by anything (yet) ask yourself why. Poke and prod the recesses of your soul. Ask yourself what matters most in the precious few decades you have left on planet Earth.

Then go and create yourself.

***

Read Next: Don’t Let Down Future You →

Footnotes

- Butler, Octavia E. “Positive Obsession.” Essence, May 1989, pp. 725–31. In Octavia E. Butler: Kindred, Fledgling, Collected Stories (LOA, 2021). Copyright © 1996 by Octavia E. Butler.

- Butler, Octavia. “Devil Girl From Mars: Why I Write Science Fiction.” MIT Articles, February 19, 1998. Accessed October 4, 1998.

- From Positive Obsession.

- From Positive Obsession.

- From Positive Obsession.

- Pressfield, Steven. The War of Art. Edited by Shawn Coyne, Black Irish Entertainment LLC, Kindle Edition, November 11, 2011.

- From her bio for the 1979 Fantasy Faire convention.