I have been in love three times. The first two were effortless and painful. The third – the one that bloomed into my marriage – was a very different beast.

For one, it was anxiety-wracking. With no outside obstacles, I agonized over the question “Is this it?” The moment of clarity never arrived. There was no bolt from the blue, no proof that I would never find someone better. I teetered, tottered, and almost lost him as a result (rightly so). In the end, I leaped because I had learned a vital lesson not a moment too soon:

Love – partnered love between two individuals – needn’t and shouldn’t be fulfilling in every way.

It’s a hard truth for a lot of us and the notion of soulmates has laid waste to countless relationships that might otherwise thrive. The truth about lasting love is counterintuitive: we’re not as special as we thought.

Or, said another way:

The other person is just as special as we are. We just need to be willing to see it.

“Spaces in your togetherness”

“Love,” wrote the intellectual giant Iris Murdoch, “is the extremely difficult realization that something other than oneself is real.”

It’s easy to blow off Murdoch’s words at first as some sort of Zen koan. But Murdoch does not mean “real” in the literal sense; she’s referring to the fact that the flesh-and-blood person standing across from you who delights you but also annoys you has an existence apart from you.

This person will notice, feel, and imagine things you’ll never have an inkling of. Their opinions and experiences will vary from yours, sometimes uncomfortably so. Just as they can never fully plumb the depths of the well that is your mind, you will never be able to fully know theirs. This unresolvable separateness is one we must embrace, even if we live under the same roof and sleep in the same bed. Especially if we live under the same roof and sleep in the same bed.

The poet Khalil Gibran gives this sage advice on co-existing:

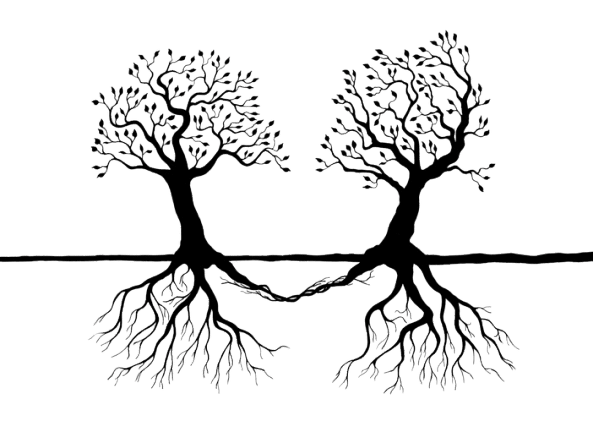

“Let there be spaces in your togetherness. And let the winds of the heavens dance between you. Love one another, but make not a bond of love: Let it rather be a moving sea between the shores of your souls.” 1

Since we can’t share souls or read minds, the best thing we can do is to recognize each other’s aloneness.

In a similar vein, in a letter to his young poet-friend Rainer Maria Rilke claims that love is “comprised of two lonelinesses protecting one another, setting limits, and acknowledging one another.” 2

“Loneliness” looks different for each of us. Some of us may think our well is deeper and harder to fill than our loved one’s. Maybe it is. What’s just as likely is that we find our thoughts and interests more meaningful since we know our minds better than anyone else ever will.

The more introspective you are, the more in danger you are of feeling alone, but there’s an even greater danger here: self-absorption. Can we know for certain that our beloved partner is not as lonely in her or his own way? Since we can’t share souls or read minds, the best thing we can do is to recognize each other’s aloneness.

In a way, this is far more powerful than being soulmates. It means choosing to love a person who is not you, who can never understand you in every way, who never will, and who also — miraculously — loves and accepts you, too.

“A recognition of singularity”

There’s an insidious connotation to the word “acceptance.”

Too often people use it when they actually mean “tolerance” or worse, “resignation.” It’s a ho-hum attitude that avoids effort or vulnerability. “He has his hobbies, I have mine.” It’s a civil way to coexist, but a sad imitation of real love.

It’s not enough to make peace with each other’s differences and lonelinesses. We must respect the qualities in our partner that are different from ours and love those qualities if possible. The differences between us of course shouldn’t be so great that we lack a foundation, but they should be enough to humble us and make us curious and grateful.

The novelist and classicist Robert Graves describes this as “a recognition of singularity”:

“Love is really a recognition of truth, a recognition of another person’s integrity and truth in a way that is compatible with – that makes both of you light up when you recognize that quality in the other. That’s what love is. It’s a recognition of singularity, I should say. And love is giving and giving and giving…and not looking for any return. Until you do that, you can’t love.” 3

There’s a beautiful double meaning here to “singularity.”

In one sense, of course, it’s the particular quality that the two of you share that attracts you to each other in the first place. But singularity also means uniqueness. It’s easy enough to love someone who’s like us. A true marker of love is to embrace someone different from us — sometimes in challenging ways — and to be glad that they are different.

When Graves adds that “love is giving and giving,” it’s no random afterthought. False love asks, “What’s in it for me?” Real love understands that this person who is different from you also accepts and loves you and your differences. It’s a trust fall. For love to flourish there must be no looking over the shoulder, scrutinizing and doubting at every turn if we’re seen and appreciated enough.

Choosing to tether your life to another person – someone who is not us, not even blood-related – and to take a genuine interest in what they think and feel is the ultimate gesture of love.

Now that I’m entering my second decade of being married, I’m learning something that may strike you as obvious but is dawning on me for the first time: the key to maintaining a lasting love requires the same qualities that make us a good listener, a good friend, a good world citizen.

Love is curious and not threatened by an experience or a point of view that’s different from ours. Choosing to tether your life to another person – someone who is not us, not even blood-related – and to take a genuine interest in what they think and feel is the ultimate gesture of love. The philosopher-mystic Simone Weil may have put it best: “To love purely is to consent to distance, it is to adore the distance between ourselves and that which we love.” 4

There never will be someone out there who believes and wants all the same things we do, who reads all the same books and loves the same pet topics, and laughs and cries at all the same things. We can choose to see this as a minus or dedicate the rest of our lives to loving the mystery and the otherness and the ongoing adventure of understanding each other in new small ways.

To exist is to be lonely in some way; how much more bearable is life if two people can love each other for their loneliness and not despite it?

***

Read Next: 4 Reasons to Not Get Married →

Footnotes

- Gibran, K. (2019). The Prophet. Wisehouse Classics.

- Rilke, R. M. (2017). Letters to a young poet: Translated, with an introduction and commentary by Reginald Snell. Vigeo Press.

- Kersnowski, F. L. (Ed.). (1989). Conversations with Robert Graves. University Press of Mississippi.

- From Gravity and Grace.