Just a five-minute walk from my home is a park, about half a mile long. Along the winding pathway are eucalyptus, deciduous, and juniper trees offering shade. On the outskirts are blooming desert willows. Near the northern tip is a small pond, home to egrets and blue herons.

I’ve walked through this park more times than I can count in the last two years. I have walked it early in the morning, at night after dark, and in the middle of the hot afternoon. I am the proud owner of a small but active dog, and I live in a small apartment. This means I have no choice but to go on at least one walk a day through this small, pleasant, but very ordinary park – during all four seasons and in all kinds of weather.

Most days that I walk are unremarkable. Often I’m still dazed from waking up. Sometimes I’m in a hurry to get it over with. Unlike legendary walking enthusiasts like Rosseau and Kant, my mind doesn’t focus on anything in particular. Brilliant thoughts don’t come to me. Most of the time I’m just focused on dodging bikers, joggers, and other dog owners.

Despite all this, I’ve noticed a slow but very real change take place. My mind has learned to take in things it used to overlook. The sameness of the itinerary means that each new detail – even if it’s just a crop of mushrooms after a rainy day – evokes a sense of intrigue and even wonder. It’s not a skill I practice intentionally. I have my dog to thank. She stops to sniff almost everything (including the mushrooms), forcing me to slow down.

Several terms are popular these days when it comes to well-being in nature: “Mindfulness.” “Stillness.” “Being present.” All of them ring a little hollow to me. Self-help experts like to push them as a shortcut to having better self-esteem, to feeling better.

But our culture suffers from an obsession with self-esteem, with helping ourselves. Irish-British philosopher Iris Murdoch, in her remarkable book The Sovereignty of Good, points out that in the wake of increasing secularization and turning away from religion, we no longer care about virtue or the “moral life” – about a greater Good beyond ourselves. “In the moral life,” she writes, “The enemy is the fat relentless ego.” 1

How do we put our fat, relentless egos on a diet? By going out into nature, of course. But nature is a starting point, not an ending point, for improving our egos. The term Murdoch uses for this phenomenon is “unselfing.”

The Power of Perspective

Unselfing is not self-obliteration or self-belittling. It’s not denying our individuality. It’s about learning how to see outside ourselves, even if it’s just for a moment.

We can do this, Murdoch tells us, by focusing on beautiful things: “Beauty is the convenient and traditional name of something which art and nature share, and which gives a fairly clear sense to the idea of quality of experience and change of consciousness.” 2

She goes on to give a clear example of how this works:

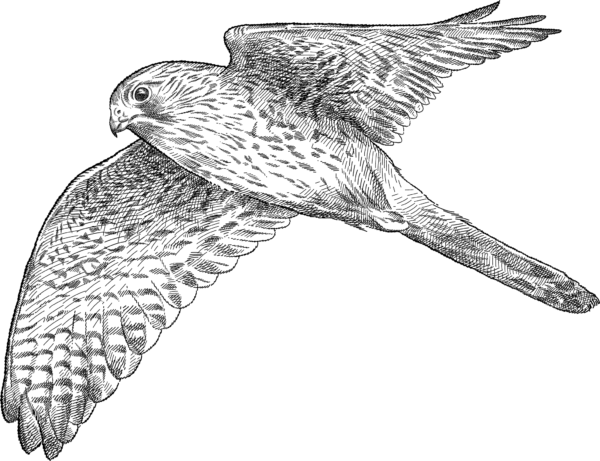

I am looking out of my window in an anxious and resentful state of mind, oblivious of my surroundings, brooding perhaps on some damage done to my prestige. Then suddenly I observe a hovering kestrel. In a moment everything is altered. The brooding self with its hurt vanity has disappeared. There is nothing now but kestrel. And when I return to thinking of the other matter it seems less important. And of course this is something which we may also do deliberately: give attention to nature in order to clear our minds of selfish care.

There are no kestrels in the park where I live in Scottsdale, but there are hummingbirds, mockingbirds, and vermillion flycatchers. Just as looking at a hovering kestrel helps Murdoch feel less irritable and resentful, the flora and fauna on my walks help distract me from my own cares and grievances. It’s not that I feel “at one” with nature; it’s that I’m reminded of my proper place in it, and in the world in general.

“In intellectual disciplines and in the enjoyment of art and nature we discover value in our ability to forget self, to be realistic, to perceive justly.”

Nature isn’t the only way to get out of our heads and pay attention to something other than ourselves. We can do this with art, too. We can do it with other people. We can do it with anything worthy of being noticed, anything with good qualities that has something to teach us.

“In intellectual disciplines and in the enjoyment of art and nature,” says Murdoch, “we discover value in our ability to forget self, to be realistic, to perceive justly.” I’m not sure what exactly it means to perceive a mushroom, or an El Greco painting “justly”, but I do know that when I look at these things and admire them, it grounds me in reality. It makes me forget about myself, and even the things I normally consider important. Even if it’s just for a few moments.

That’s the power of unselfing: a chirping sandpiper, a unique sand sculpture, or a blade of grass with a ladybug perching atop it has the ability to make us humble without humiliating us. Our big fat egos shrink in the face of something so pure and unpretentious.

Unselfing Is Seeing Things As They Really Are

In The Sovereignty of Good, Murdoch heavily references Plato, his Forms, and his allegory of the cave. “The self, the place where we live is a place of illusion,” says Murdoch. “Goodness is connected with the attempt to see the unself, to see and to respond to the real world in the light of a virtuous consciousness.”

Just as the sun is real and shadows are not, we want to see other people and creatures as objectively as we can. The question is, is such a thing even possible? How do you look straight at the sun without burning your corneas off?

Murdoch admits that this is not perfectly possible. Not on this flawed planet, not for any significant amount of time, anyway: “It is an empirical fact about human nature that this attempt cannot be entirely successful,” she admits.

Even so, we can still get a glimpse of things as they really are. We can temporarily rise above the relentless humdrum of our own self-focused, anxious, repetitive thoughts. Perhaps that’s what art historian John Ruskin meant when he said:

The greatest thing a human soul ever does in this world is to see something, and tell what it saw in a plain way. Hundreds of people can talk for one who can think, but thousands can think for one who can see. To see clearly is poetry, prophecy and religion, all in one. 3

I don’t really think of myself as a poet, prophet, or wise woman when I’m entranced by the sight of a sunset or (as I was recently) a hawk sitting atop a pine tree. But at least, in that moment, I’m being a little less petty, a little less selfish than I am normally. My big fat ego is just a little bit leaner. And I feel just a little bit less alone in the world.

Read Next: Why Leisure Is More Important Than Work →