Diogenes of Sinope was one of the more colorful ancient philosophers.

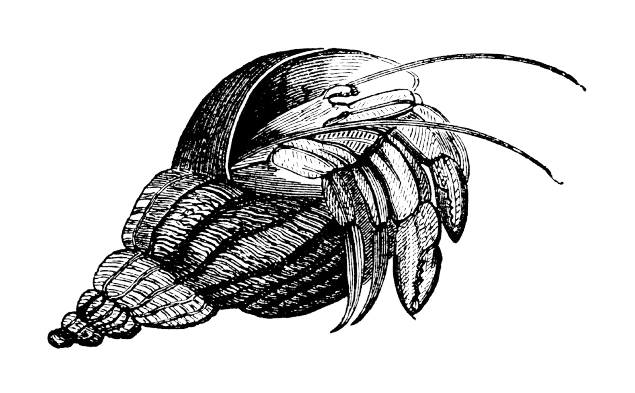

He lived a threadbare existence by choice and got all his food from begging. Instead of a house, he lived in a large ceramic jar (a genus of hermit crabs is named after him for this reason). “He has the most who is content with the least,” was his life motto. When Alexander the Great once famously asked him for whatever he wished, Diogenes asked the infamous conqueror to step aside because he was blocking the sun.

While Diogenes is the poster boy for a life of minimalism, he’s far from the only one with opinions on contentment. “He who is not content with what he has, would not be contented with what he would like to have,” quipped Socrates, Diogenes’s forbearer. “Contentment is the greatest wealth,” the Buddha affirmed.

Millennia later, we find similar examples: Thoreau, retreating to his 150-square-foot cabin on Walden Pond, declared, “A man is rich in proportion to the number of things he can afford to leave alone.” Nietzsche took it even a step further and embraced his belief in “amor fati”: loving your fate and wanting your life to be no different than it is – even when you’re broke, single, and in horrible chronic pain.

Good for them, but what about progress, innovation, and self-improvement? “Contentment” is an elusive concept; most of us agree that it matters, but not on what it means. Are Socrates and Buddha saying we can’t have nice things? Since they aren’t around today to expound, our task is to use what wisdom and common sense we have to define what “contentment” is.

Contentment as an emotional state is probably impossible for most humans – especially long-term. You’re just not going to feel content going about your day-to-day as you stub your toe and deal with sugar cravings. Contentment, rather, is an attitude. A way of operating through life. You can take it to the extreme like Diogenes and shun anything you don’t technically need. Or you can be more practical like the Stoic philosopher Seneca: acquire all the wealth you want, but just as easily shrug it off when you’re exiled to a small home on a tiny island.

I offer the following three thoughts on how we can achieve contentment without being like Diogenes (although by all means, live like Diogenes if that’s calling to you).

Choose Your Wants Carefully

The problem isn’t wanting things; the problem is wanting things without knowing why you want them. It’s true that the less we want, the more easily we’re contented. It follows that we should choose our wants carefully.

What is a want and what is a need?

This is where we start confusing one for the other. Do we need to earn $250,000 a year to be safe and secure, or is psychologist Daniel Kahneman right when he suggests the number is closer to something like $75,000? 1

In some cases, it’s easy to tell the difference: you may want a Tesla Model Y, but you don’t need one to get around town. What if you don’t have a car at all? Do you need one, or is that still just a want? Diogenes would probably have declined to ride even a scooter, but we are not Diogenes. Is it too much to want a mid-sized SUV? This is the grey area of “want versus being content.” It takes a lifetime of wisdom to know the difference.

This doesn’t mean that it’s bad to have wants, either. We don’t have to live in a tiny home or a ceramic jar or even a condo; if a larger home is within your means, by all means, live in one – as long as you’re not overly attached to it. The Stoics used the more clinical term “preferred indifferent” to describe wants: something that’s nice to have, but not vital to our well-being. The easier it is to control our wants, and distinguish them from needs, the less empty we will feel.

Choose your wants carefully.

The Opposite of Contentment Is Obsession, Not Ambition

A world with a few Diogeneses can function just fine because there are other people to provide food (and make large ceramic jars). A world in which everyone is Diogenes wouldn’t look much different from the Pleistocene era. We are born with the drive to create and improve, and there’s nothing wrong with that.

Ambition is not the enemy of contentment; obsession is. One is healthy and productive and means that we care about something enough to work for it and possibly have our hearts broken in the process. The other is an eternally moving target, a fixation on what isn’t, an itch that can never be scratched. 2

What if you’re not sure whether you’re ambitious or obsessed? Here’s a helpful metric: how realistic is it? How much control do you have?

Writing and polishing a complete epic fantasy series is a staggering amount of work, but it is without our reach (assuming our health and lifespan hold out). Winning the Hugo Award or being on the New York Times Bestseller List for 40 weeks straight, on the other hand, is not. That’s the difference.

Contentment is compatible with wanting something, if we can execute on achieving the thing we want. Wanting something out of our control is obsession. And never wanting anything or trying for anything is complacency. Neither of these things is compatible with contentment.

Contentment Is In the Pursuit, Not the Outcome

The psychologist Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi (with all due respect, I hate typing his name) has probably done more to shed light on the topic of happiness for a modern audience than any other writer I know.

In his now-famous book Flow, he explains that we get our sense of well-being from the process of doing things, not in getting things: “If a person learns to enjoy and find meaning in the ongoing stream of experience, in the process of living itself, the burden of social controls automatically falls from one’s shoulders.” 3

That’s why you feel better after planting your own strawberry patch or going on a hike than you do after watching TV – you are working and creating. What does this have to do with contentment?

I think when the word “contentment” flashes through most people’s mind, they’re envisioning a passive state: someone in lotus position sitting perfectly still until a bodhi tree, a Diogenes in his jar. But contentment is very much a principle of action. At the risk of sounding obvious, we are never done with doing things until we’re dead. Life is not static, and so it doesn’t make sense that contentment is a static, final state either.

Contentment is not a destination nor is it a goalpost that moves as soon as we reach it. We can be content at any given moment even as we are reaching, grasping, hoping, and striving. Diogenes was right that the less we want, the easier life is. But wanting is what makes us human and capable of extraordinary things. We needn’t sacrifice contentment for achievement as long as we’re careful and wise.

***

Read Next: Is It Bad to Watch TV? →

Footnotes

- Kahneman, D., & Deaton, A. (2010). High income improves evaluation of life but not emotional well-being. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 107(38), 16489-16493. Note, $75,000 adjusted to inflation today is closer to $100,000.

- And, I’ll add, the enemy of ambition is “complacency.” The next time you’re arguing about contentment with someone, make sure you’re not confusing the two.

- Csikszentmihalyi, M. (2008). Flow: The Psychology of Optimal Experience (1st ed.). Harper Perennial Modern Classics.

One response to “On Contentment: A Riddle for the Ages”

This was great! Thanks