In the late 1960’s, a psychology professor at Stanford University conducted a deceptively simple experiment:

In a small room hardly larger than a closet, a four-year-old child was invited to sit at a desk and choose either a marshmallow, a cookie, or a pretzel stick from a plate. The child was then given a simple offer: she or he could either eat the treat immediately or wait a few minutes and get an additional treat.

The results weren’t too surprising. While about 30% of the children were able to hold out, the rest of them gave into temptation and gobbled the treat down. Some didn’t even bother to wait and ate theirs immediately. Others tried distracting themselves by looking away or kicking the table.

Today, the experiment is so famous that many people simply know it as “the Stanford Marshmallow Test.” But at the time even Walter Mischel, the professor in charge of the experiment, didn’t realize just how profound its impact would be.

Over the next several years, during dinnertime with his three daughters, Mischel would ask them about their friends – some of whom were participants of the Marshmallow Test. He began to notice a pattern: the friends who did well in school tended to be the ones who had shown greater self-control during the marshmallow experiment, compared to the ones who hadn’t. Realizing that he was onto something big, Mischel reached out to as many of the marshmallow experiment subjects as he could to do follow-up questioning.

Here’s what Mischel and his team learned over the next several decades of study: The way we adapt and endure through life is much more important to success than our intelligence is.

“What we’re really measuring with the marshmallows isn’t will power or self-control,” Mischel revealed to an interviewer. “It’s much more important than that. This task forces kids to find a way to make the situation work for them. They want the second marshmallow, but how can they get it? We can’t control the world, but we can control how we think about it.” 1

Although Mischel never uses the actual word, “patience” is very much at the heart of the Stanford Marshmallow Test. But as he and his team discovered, patience is much more than simply waiting, or using sheer willpower. It requires strength, resilience, and creativity. Its results are powerful, but they only come after some time.

In the hectic 21st-century times we live in, patience has perhaps never been more overlooked. It’s also never been more needed.

Patience Isn’t Passive

We’re all familiar with the old saying, “Patience is a virtue,” but how many of us take it seriously?

Both “patience” and “virtue” have old-fashioned connotations. We name baby girls today Grace, Hope, and Faith, but Patience hasn’t been a popular choice since the Victorian ages.

Part of the problem is rooted in definition: many people today think of patience as simply waiting. “Be patient,” we tell our squirming child as we get dinner ready. “Be patient,” we tease when we’re about to surprise our significant other. We mistakenly think of patience as just holding our horses for a little while longer.

In an age of smartphones and instant gratification, patience might seem outdated, even unnecessary. We might see patience as being weak or passive in the face of the ever-growing problems and injustices in our world.

The problem with all these views of patience is that they are very one-dimensional.

In reality, patience is an extremely dynamic and active principle – it’s just not a very visible one. Patience is far more than biting your tongue or sitting still; it’s a cultivated state of mind that changes how we see the world. The ancient Stoics knew this. So did the Buddhists. So did the cloistered monks of the European Middle Ages. 2

Patience is a vital key to both growing as a person and staying sane in an ever-fluctuating world. If you still find the word “patience” unsexy you can exchange it for “calm,” “open-minded,” or “persistent,” but all of them are different aspects of the same greater concept.

In his book On Patience, philosophy professor Matthew Pianalto describes patience as having many qualities far beyond simply “putting up” with difficulties. Patience not only helps us endure challenging situations but it helps us adapt and be creative in those situations. It’s a skill and a mindset that make us better people. “To seek what is good, to recognize it, to hold fast to it – all of this is the work of patience.” 3

Pianalto argues that it even makes us better people:

“[P]atience also encourages us to broaden our vision, to listen to what others are too busy or too upset to hear, to cultivate a stillness of mind that makes it possible for us to be receptive to new ideas, to learn from others, and to make sense of our own thoughts and experiences. In these ways, patience draws us out of ourselves and our own specific pursuits and concerns so that we avoid narrow-mindedness and dogmatism.” 4

On the surface level, being a more patient person might mean being more courteous in traffic or in conversation with others.

At the deepest level, though, patience is about how we see the entire world and grow as individuals. Perhaps that is the most remarkable thing of all about patience: the power it has to transform us over time.

Patience Is Power

Would you be able to stare at the same painting for three hours?

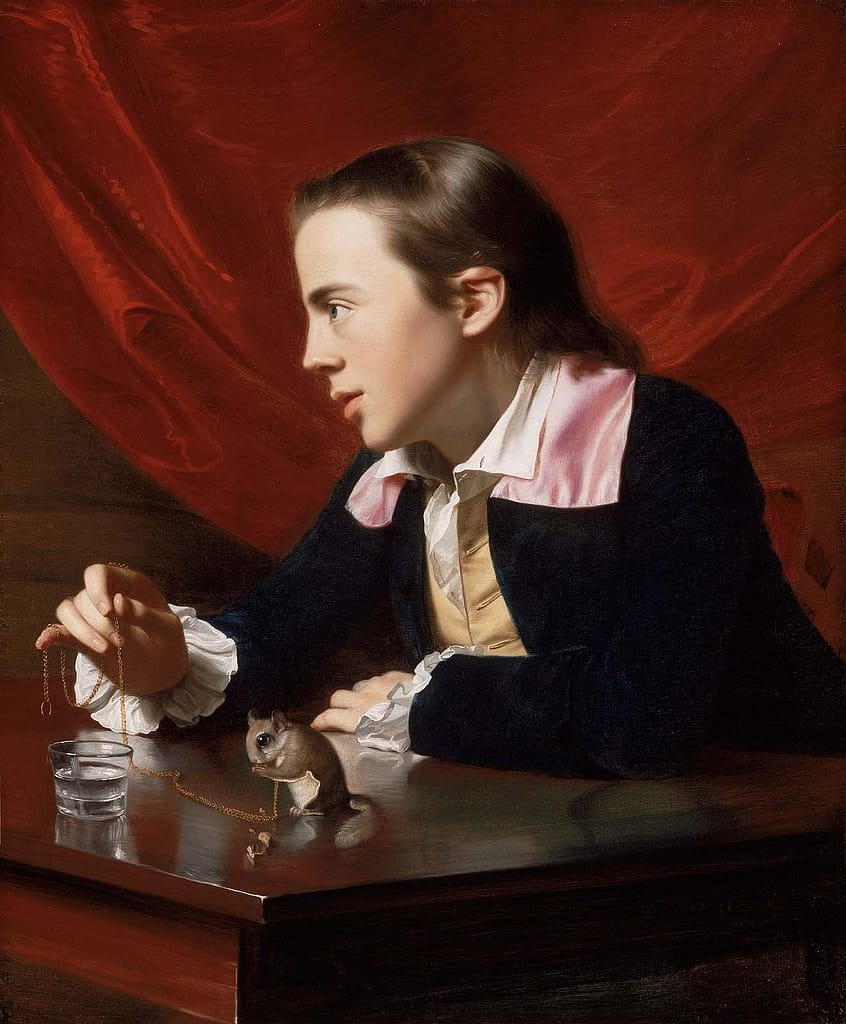

That’s exactly what Harvard art historian Jennifer Roberts challenges the students in her art class to do. One of her favorite artworks to assign is Boy with a Squirrel by John Singleton Copley, a painting that looks fairly simple at first glance.

Most of her students struggle at first. Three whole hours? That’s what most of them are thinking. How much can I even find after three hours?

The answer is a surprising one. The students who follow Roberts’ assignment discover many details and insights that are only noticeable after spending that much time looking at the same subject. What the exercise does is force the viewer to slow down and be more intentional about what they’re doing in the first place – Roberts calls this “deceleration.”

The payoff for this type of patience is tremendous. It helps develop students’ critical thinking skills and gets them into the mindset of questioning things instead of immediately accepting or assuming. It teaches them to pay attention, dig deeper, and try harder.

For Roberts, patience is “an active and positive cognitive state…it is a form of control over the tempo of contemporary life that otherwise controls us. Patience no longer connotes disempowerment—perhaps now patience is power.” 5

In other words, if we do not take the time to practice controlling our thoughts and actions, the chaos in the world around us will control us.

Patience, as both Walter Mischel showed us with his Marshmallow Test and Jennifer Roberts showed us with her artwork exercise, is about far more than willpower or simply not doing something.

It’s about consciously slowing down and choosing how to think, act, and react in a world that will never slow down for us. It’s about making decisions today that will benefit us years from now. It’s about growth and discovery.

“Patience is the root and the guardian of all the virtues,” Gregory the Great declared back in the 7th century. Whether or not you agree with Saint Gregory, patience is a powerful skill that will help you go much further in life than you might otherwise.

***

Read Next: Is It Good to Be Alone? The Paradox of Solitude →

Footnotes

- Lehrer, J. (2009, May 18). Don’t! The New Yorker. https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2009/05/18/dont-2

- So did the most successful children in the Stanford Marshmallow Test. The ones who held out the longest weren’t the ones who simply sat and suffered; they were the ones who found creative ways to re-focus their thoughts and attention so they wouldn’t be as bothered by not getting to eat the marshmallow right away.

- Pianalto, M. (2016). On Patience: Reclaiming a Foundational Virtue. Lexington Books

- On Patience, pg. 134

- Roberts, J. L. (2013, October). The Power of Patience. Harvard Magazine. https://www.harvardmagazine.com/2013/10/the-power-of-patience